By Wolves in the Walls director Pete Billington

Before we embarked on our journey to create Lucy, we reached out to anyone who had attempted anything remotely similar in the past. It’s unclear whether we were seeking advice, or secretly hoping to be told we were attempting the impossible. We are big fans of Elizabeth of Bioshock fame and were extremely fortunate to be able to share early versions of Lucy prototypes with Jordan Thomas, one of her creators. We also spent some time with Doug Church, who had worked with Steven Spielberg on an ambitious character called Eve for a project codenamed LMNO. Elle from Last of Us was another touchpoint.

While each of these characters represented huge advancements in game-based interactivity, they were all character-companions, and not leads. In game play, the player is the lead. We wanted to turn this player-character relationship 180 degrees and make Lucy the main character. As Lucy’s imaginary friend, the audience would assume the role of companion to her lead.

We also decided that we never wanted Lucy to “gate”. This was a distraction that we repeatedly observed with puzzle-based interactions; a character often seems stuck in some sort of seizure-loop, while it waits for the player to do a required task to advance the narrative. We will always and forever refer to this as Shooting the Hinges. We wanted Lucy to feel natural and intuitive and not wait for the audience to complete a task. It also removed the pressure to make a “right” decision. This can encourage extroversion and risk taking. It also places a large burden on the animation and interactive teams to provide branching alternatives to a single “right” decision.

There were two main objectives at the start of Wolves in the Walls. The first was to build upon the VR-based character connections that were developed for Henry. The second was to figure out how the audience would use the yet-to-be-released Oculus Touch controllers. This meant the audience would be using their hands. But for what purpose?

Everyone who develops for Virtual Reality has had at least one “moment.” We have had more than a few while working on Wolves. The first came with a very simple flashlight prototype. Using a very early version of Lucy, we simulated a fuse blowing and the lights going out. A panicked Lucy desperately hands us a flashlight. We found that everyone grabbed the light without hesitation and then marvelled at the ability to illuminate Lucy’s world. It was magic. We immediately knew there was something powerful in this object/character interaction.

A second early test had Lucy probing the wall with a tin-can telephone while she offers us the other end.. As you move the can toward your ear, you can hear the ambiguous sounds an old house makes transforming into wolfy howls. This was the first time we knew sound was going to be crucial to the connection to this little girl.

AN AMBITIOUS PLAN

We were incredibly encouraged by these early tests and we developed a strategy for how we would build Lucy. Character pillars were created with the purpose of keeping us on course:

Lucy should....

Deliver a believable, specific emotional performance

Maintain the illusion of life independent of the linear narrative

Relate to her surroundings in an non-deterministic way

React to audience agency in a way that is consistent with her passions

Appear to have a memory of previous events

Evoke a sense of deliberate, stylized consistency in design, behavior and performance.

Delivering a believable specific emotional performance was something we had been doing as animators and filmmakers. But maintaining that illusion outside of the linear narrative is where things got more challenging. If we could make Lucy’s emotional preferences push her towards believable actions, it would seem like she was more of an actress and less of a robot.

We wanted to create a “Smart Environment” that could inform Lucy about how to feel, what to do and where to look in her world. We also wanted to create an emotional system that disconnected dialog from mood and could change tone relative to audience choice.

Memory was, and still is the cornerstone of Lucy. We needed to make sure the audience felt like their actions had consequences. Even at the earliest moments we believed that memory was the key to meaningful connection.

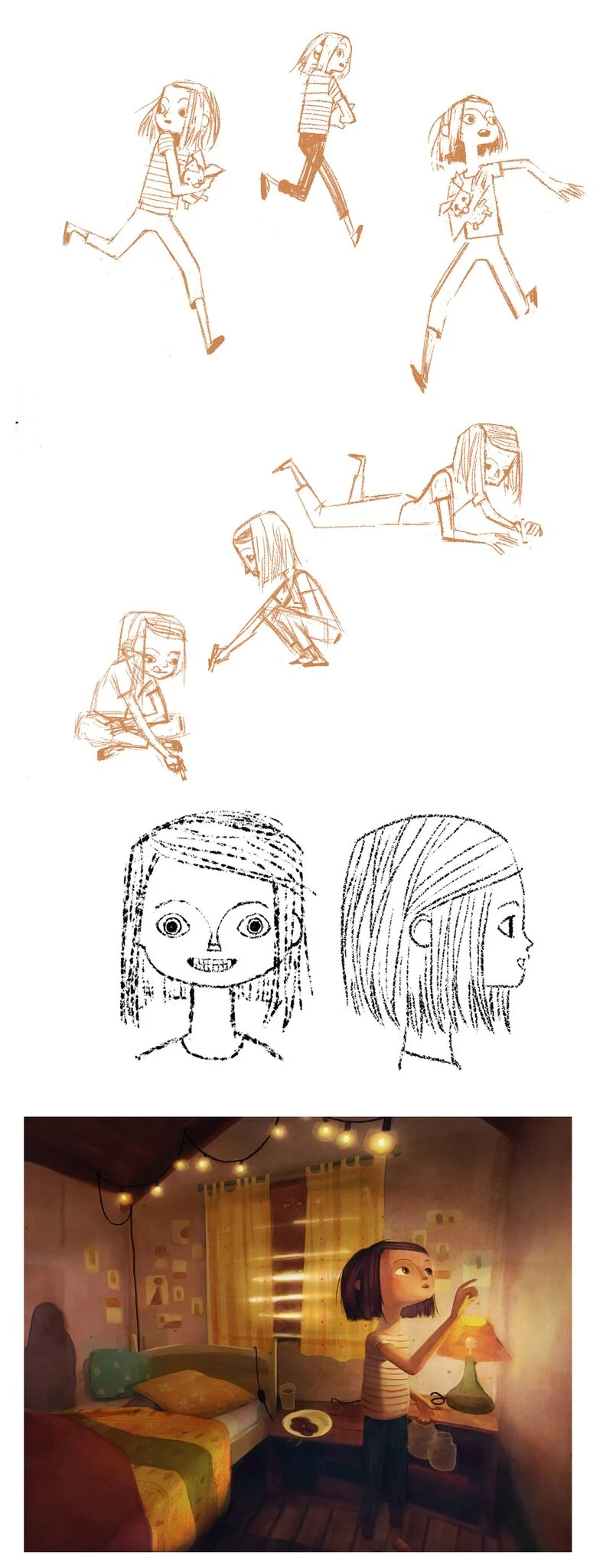

Finally, we knew, having worked on many virtual characters prior to Lucy, that the pitfalls of the “uncanny valley” are related to inconsistency. Any time two or more components fall out-of-phase with each other, the entire system breaks down. We deliberately set out to stylize Lucy in all aspects of her being.

While these ambitions were honorable, they weren’t necessarily achievable within budget and deadline. Nor were they particularly informed. They were mostly hypotheses, as no one had attempted to do this with a character in Virtual Reality. After a handful of early prototypes we embarked on a six month test to see how far we could get. This test, referred to internally as RA4, was the single most significant failure of the project.

As our familiarity with the Touch Controllers grew, we started to fall in love with (virtual) objects. We developed a theory that objects had secret lives and could tell stories. Certain objects have deep emotional connections for their owners. For Lucy, no object was more connective then her Pig Puppet. Pig was becoming a central part of the story, and we used him to test this theory.

In RA4, Lucy is next to her detective desk, examining a slew of evidence. A group of objects are arranged in an appealing display in front of the audience. A magnifying glass, and antique stereoscope, a instamatic camera, and Pig Puppet. The audience can pick up an object, and depending on its emotional weight, Lucy will react accordingly. Depending on how you treat the object, Lucy’s mood may change. If you mistreat Pig Puppet, Lucy will become frantic and try and take him back. At some point, Lucy hears noises and the narrative resumes.

Our theory about the emotional weight of objects was correct, but this prototype failed because the objects were too distracting and disconnected from the narrative. We learned that interactions that connected you directly to Lucy, (like the flashlight example) were both incredibly powerful and also compatible with the narrative.

We started referring to these connection points as natural-intuitive interactions. Things that we do without thinking, like flipping on the lights when we enter a room or reaching out to brush away a cobweb. While writing these moments can be relatively straightforward, designing an interaction system to support them is incredibly difficult.

We knew that we needed a complex head and eye tracking solution. In virtual reality we share a space with a character, so eye contact is much like the real world. Social conventions needed to be upheld. Lucy couldn’t look at us for too long or it would seem bizarre or creepy. We observed team members during casual conversation and measured how far our eyes move before our heads do. Lucy also needed to know where the audience was in the space, what they were holding, what they had dropped, whether they had taken a picture or were simply distracted and looking the other way.

To handle the seemingly infinite edge-cases that interactive VR presents we authored an attention-interest system that allowed Lucy to be interrupted but would also give the animation team a level of hand-crafted control that could keep her alive and appealing.

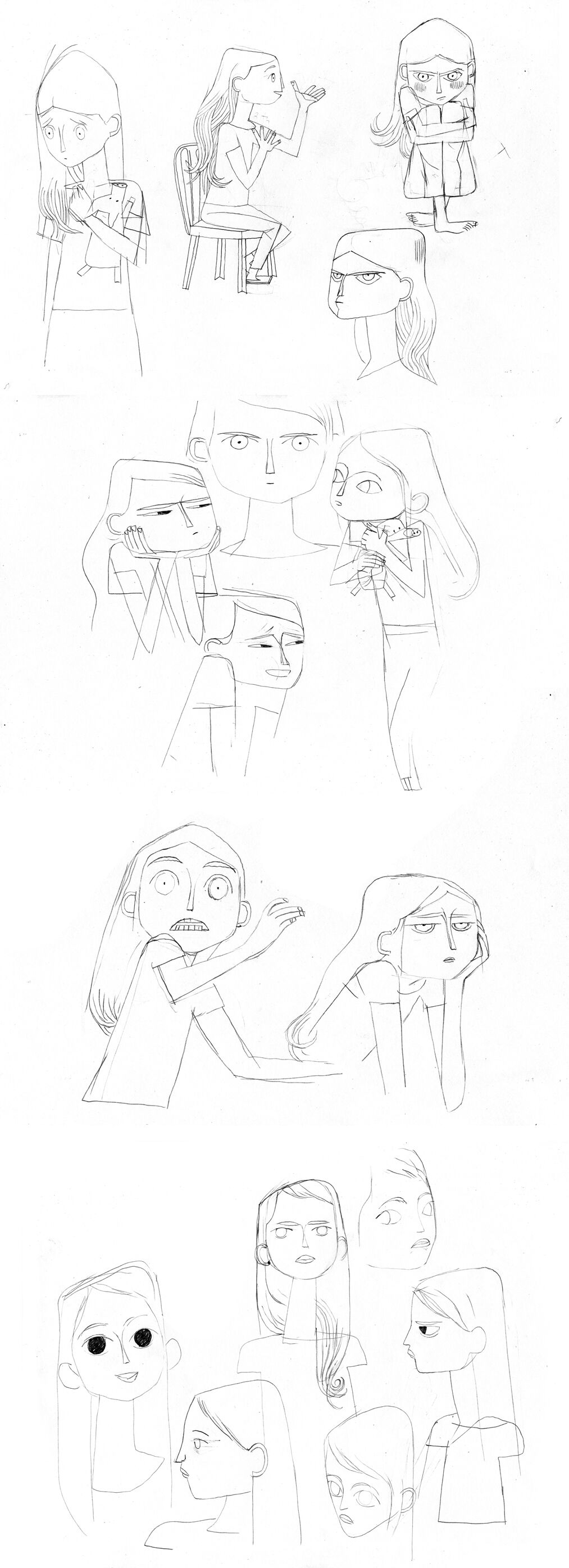

Production Designer Kendal Cronkhite is a master at appeal. She has a magical ability to de-digitize computer generated characters. As the designs for Lucy evolved, we started viewing the character in Virtual Reality. There are so many techniques that need to be altered when you share a space with a character. The smallest proportion changes have a huge impact. Hands and eyes are incredibly important and the design process becomes much more instinctual, relying on our deep-human perception skills rather than our design experience.

As we delved into the adaptation of Neil Gaiman and Dave Mckean’s storybook, we found that we wanted Lucy to be more vulnerable. In the original illustrations it is difficult to determine how old Lucy is, and at first we made Lucy the older of the two children. But it is often the youngest in the family who see things the clearest and yet are ignored the most. This seemed like the appropriate plight for Lucy, and so, very late in the process, we made her four years younger. This risky decision was partially informed by a precocious eight-year-old voice actress that we simply couldn’t get enough of.

Changing Lucy’s age had huge implications. The first thing that happens to you in the experience is you are scaled down to Lucy’s size. This means that the world gets much bigger. (in a virtually-relative sense) But in this way, we see the world through the eyes of a child, and since we are Lucy’s imaginary friend, we see the world through her eyes.

This led us to our next major unlock. Emotional Point of View, or Emotionally Subjective Cinematography. Because we are Lucy’s imaginary friend, we see the world the way that Lucy feels the world. This means that depending on Lucy’s emotional state, the environment may change to feel more scary or intimate. Lucy and the environment are inextricably connected and part of the same emotional state. Environment becomes a direct extension of her character.

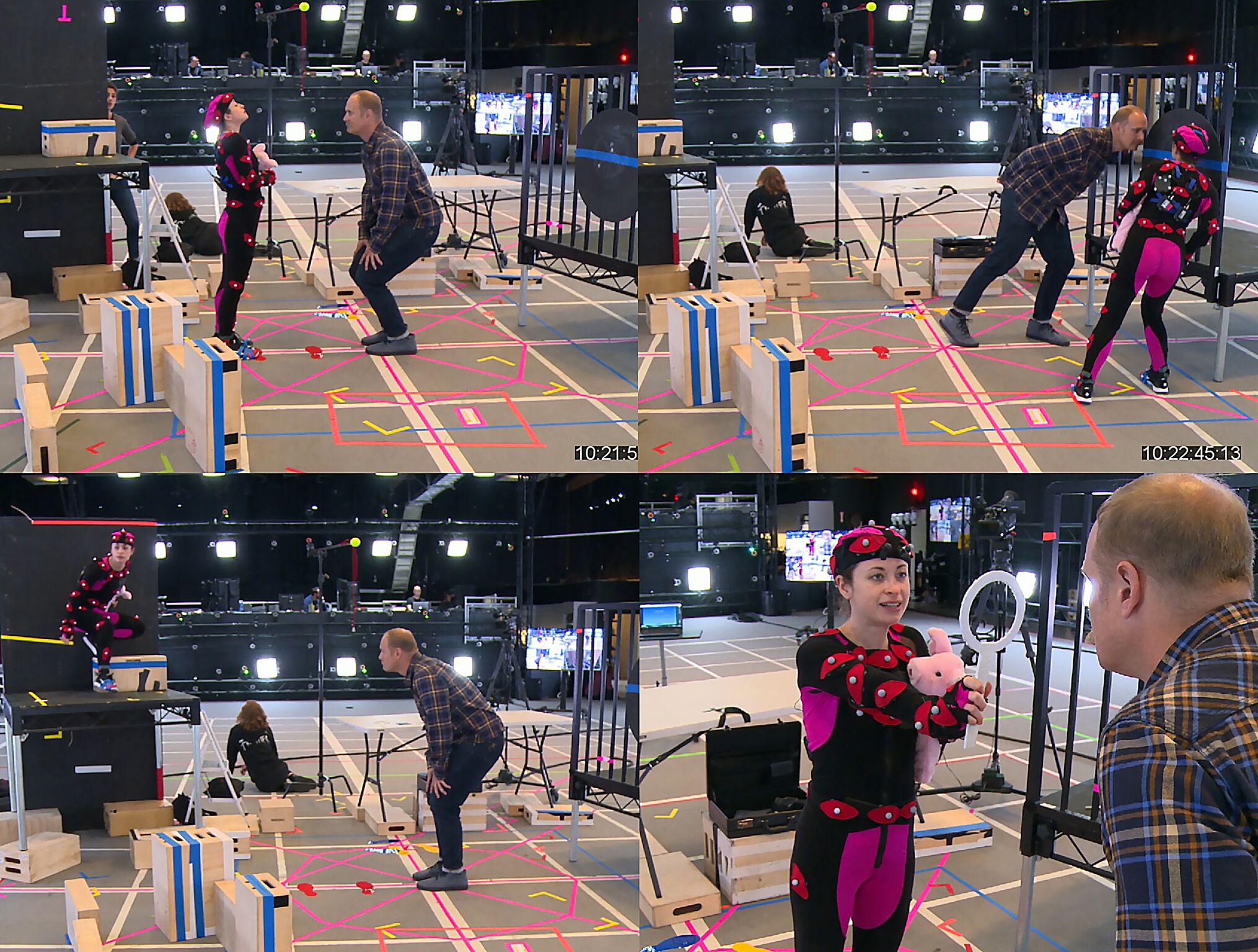

Ultimately Lucy would be driven by a complex weave of motion capture, hand animation and procedural systems. Before that could happen, we need to design how she would move. During early development we realized how similar theater and dance performance were to Virtual Reality. When a dancer moves through space they must be aware of how the audience perceives that motion relative to their position. This is different from the composition of a two dimensional rectangle of cinema.

We were incredibly fortunate to collaborate with Third Rail Projects in both the ideation and choreography of Wolves in the Walls. When we motion captured the body performances for Lucy, we used theatrical and dance technique to keep Lucy in constant motion. The whole experience is intended to be a dance, enveloping the audience. Lucy always arrives exactly where you need her to be and then continues to flick and dart around the space.

Once we had the performance captured, the animation team needed to breathe personality into Lucy. Animation Supervisor Jamee Houk spent months developing a facial library that fused the quirky eight-year-old voice of Cadence Goblirsch and the fluid dance perfomance of Elisa Davis. The result is some sort of alchemy that manifests Lucy into our world. You completely believe that she is there, and that she really needs your help.

Once we were regularly spending time with Lucy, we started to miss her when she wasn’t part of our day. She was becoming our friend. It’s a strange phenomenon, watching this virtual being grow and learn. You become very attached and want to know that she is ok.

In one of our experiments, Lucy and the audience play tic-tac-toe together. You can pick up a crayon and mark an X or an O on the grid. Lucy knows which one you drew and plays the opposite. She’s actually quite good. (beating one of our animators on multiple occasions). She also knows when you cheat, gets bored when it’s a tie and pouts when she loses. While this is a very simple AI driven prototype, it reveals the potential for a much deeper relationship with a character like Lucy.

When we show Wolves to people, we often observe them talking to her, sometimes openly and in unexpected ways. All of this points to a future where people will have ongoing, persistent relationships with characters across all types of media. It is something that we are very excited to explore.

The idea of this character who can experience and then store memories, recall them, and then tailor the next encounter accordingly... It has vast implications. We could have relationships with characters that could evolve over decades. Relationships where we form complex emotional bonds, where we could learn and grow with each other, face our fears together, share our dreams. We are hopeful for a future where someone as brave and admirable as Lucy is always there for us.